Before the 19th century, the standard place of burial involved an overcrowded churchyard stuck in the middle of a city. Not exactly a location one would enjoy visiting to pay respects to a loved one, these "places of rest" were much more chaotic and crumbling than peaceful or inviting.

This stone has been chosen to be observed according to Applebaum's quandrant chart.

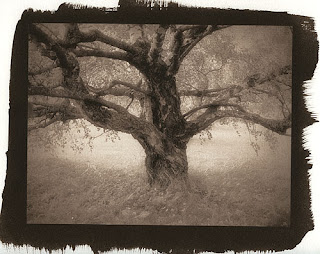

Frost spalling, or wedging, is another real danger for stone. This occurs when water fills small cracks and then freezes, which breaks the rock.

There has also been some weathering on the intricate carvings on the stone, which have been rounded an smoothed out from wind and rain.

A missing acorn from the design can be seen here:

In the past, primaraly before the 17th century, gravestone iconography held fast to more Puritan views, which involved contempt towards ones life on earth, and a resignation in the face of death.

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, a shift towards the Romantic gave way to a much more hopeful and romanticized idea of death and the afterlife. In the late 1800s grave stone decoration reaches its peak, as stones become highly intricate and detailed.

For this particular grave, one can see signs of such intricacy and effort being put into the stone.

The oak leaves around the outside are said to represent strength, endurance, faith, and virtue, and the acorns convey prosperity. All of these are meant to portray the family in a positive light.

Stone restoration and cleaning is a controversial topic due to the fact that there are a large number of factors that can result in additional damage to the stone." A number of authors have emphasized the damage that can be caused by cleaning: loss of surface, staining, deposition of soluble salts, or making the stone more vulnerable to pollutants or biological growths" (Price).

This beautiful and decorative memorial of the life of Marianne Keister is just one of many nestled among the grassy hills of Mount Hope that is doing its best to stand the tests of time.

Guidelines for Evaluating Cemeteries National Register Bulletin

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/do_history/graveyards/index.cfm

Price C. Stone Conservation